The barriers to solving your business problems: Part 1 – Problem recognition

By Peter Meyer, Principal Consultant, Elkera Pty Limited

23 July 2025

Many medium-sized organisations face critical strategic challenges.

Some are struggling to keep up with rapid growth because their structures and systems haven’t kept pace with their increased scale and complexity. Others, particularly not-for-profits, face pressure to reduce costs while maintaining service levels.

In both cases, organisations often show recurring symptoms:

- Disconnected systems, duplicated effort, and manual work that could be automated.

- Unclear or misaligned roles, leading to duplication, poor communication and unproductive behaviour.

- Insufficient data for managers to make informed decisions.

- Quality issues, customer complaints, and customer attrition.

- Poorly documented processes and slow onboarding.

- Low staff morale, diminished performance, and high staff turnover.

- Limited innovation in products, service delivery or process improvement.

The costs of these problems accumulate over time. Some could be addressed without major financial investment, through better structure, accountability and process clarity. Others do require well-planned investment in systems and tools.

Unfortunately, many medium-sized organisations fail to resolve those problems, even where little capital investment would be required.

Instead, there is a pattern of quick-fix actions that focuses on symptoms rather than the underlying causes.

What prevents otherwise capable leaders from taking a more systemic approach to solving their business problems?

In this article, I consider three key factors as the source of this problem:

- Problems are not visible due to internal structural barriers

- Leadership pressures and incentives promote short-term behaviours

- Lack of systems thinking.

1. Problems are not visible due to structural barriers

In many medium-sized organisations, the organisational structure has evolved as the business has grown. There may not have been a formal process to design the organisational structure. Functions and responsibilities are often distributed based on personalities, history, or perceived operational convenience, rather than on a clear functional model.

Functions in a production process may be divided within distinct work units that may operate in a siloed way. While work units may all work together to produce business outputs, they are not organised in a systemic way to do so optimally.

Siloed structures introduce multiple problems:

- Obscured overview: Senior managers may not fully understand how functions are performed and have no overall view of problems. They are dependent on information provided by each team manager who may have little interest in processes outside their responsibility.

- Local focus: Teams are likely to devise their own workflows and practices without adequate consultation or concern for the interests of other teams.

- Duplication of effort: Two or more departments may manage overlapping processes or data, each using their own approach.

- Responsibility gaps: When responsibilities are not clearly assigned to defined business functions, accountability becomes diffuse and key tasks may be overlooked.

- Suboptimal staffing: Based on historical factors or internal influence, some teams may have excess staff while others are insufficiently staffed.

When the structure is unclear and siloed, neither team leaders nor senior management have reliable way to see how the parts interact. When each manager addresses issues within their remit, but without a coordinated view, the organisation lacks the means to diagnose system-wide problems.

2. Leadership pressures and incentives promote short-term behaviours

Most leaders in medium-sized organisations face strong incentives that pull them towards a focus on short-term results. This is particularly strong in:

- Organisations facing immediate financial stress or funding pressures

- Not-for-profits required to meet annual targets defined by funding bodies

- Fast-growing firms where there is little time for reflection.

Under those pressures, short-term action is prioritised over long-term, strategic thinking. Leaders may be stretched too thin to step back and consider issues from a structural or systemic perspective.

Systemic change requires time, attention and determination.

3. Lack of systems thinking

If organisational structure is unclear and siloed, as described earlier, that means that no one has taken a systemic view of the organisation. It is viewed as discrete parts, rather than as a whole.

Systems thinking is a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts. [Wikipedia, “Systems thinking”]. Systems thinking studies connections between key parts to see the collective behaviours that result [Six Sigma.us 2024].

Few managers are trained in systems thinking. Instead, most are taught to break problems down into discrete, solvable units. That can work well for many issues, but not for business performance challenges around product or service delivery and related organisational structure. Where there is a high level of complexity and interdependency, a systems thinking approach is required.

Lack of training is only part of the problem. Lack of systems thinking is associated with cognitive biases that unconsciously shape how problems are defined and addressed [Praslova 2023].

Rather than see problems as systemic, leaders may view them as caused by unsatisfactory staff behaviour. In that way, the problem is personalised, providing an apparently clear target for corrective action. For example, if a leader believes that customer complaints are due to staff behaviour, they may overlook underlying process or system failures. This approach is likely to lead to a blame culture that undermines learning and accountability [Louvion 2023].

Without a systems perspective:

- Problems may be framed too narrowly around visible symptoms like delays, complaints, or errors, without understanding the root causes. A blame culture may develop.

- Improvements may be undertaken in a fragmented way and without assessing how they interact with other parts of the business.

One of the clearest examples of a lack of systems thinking occurs when an organisation is under pressure to cut costs. Rather than apply a systemic approach to reducing costs, the CFO or COO may demand that each department head reduce staff costs by a certain factor. Responsibility is thus devolved to departmental heads, each of whom has a limited visibility of the broader system. It may produce quick results in the short term but it is unlikely to be effective in the longer term, as I explain in a previous article [Meyer, February 2025].

Systems thinking doesn’t mean doing everything at once. It means analysis and planning from the top by recognising the organisation as a collection of functions and process flows that must work together to produce the desired outputs.

Conclusion

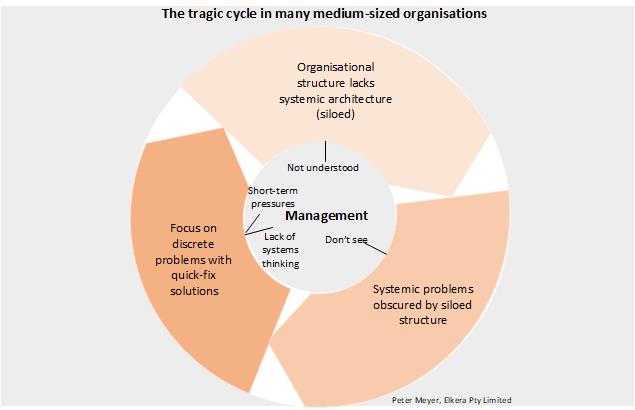

The three factors described earlier create a cycle under which the real problems are never solved. This creates what I call a ‘tragic cycle’, a self-reinforcing loop where symptoms are treated, but causes remain untouched. That cycle can be visualised in the diagram that accompanies this article.

The pressures facing medium-sized organisations are real. The temptation to act quickly is understandable. But when solutions are driven by siloed thinking, an absence of systems thinking, and short-term incentives, organisations risk wasting money and failing to address their real problems.

The key barrier to recognition of an organisation’s problems is ultimately based in a lack of systems thinking. Once a systemic approach is adopted:

- the problems related to an existing siloed structure will become clearly apparent, and

- leaders should be able to recognise the effect of short-term influences on their actions.

A systemic approach to the organisation will support better decision making through:

- An understanding of the structure and function of the business

- Clarity about the sources of problems

- A clear framework to prioritise and plan organisational structure and problem resolution.

Systemic problem-solving is available to any organisation. It begins with a shift in perspective from a focus on parts to the whole.

In a counterpart to this article: The barriers to solving your business problems: Part 2 – Removing the barriers, I describe the steps can leaders take to adopt a systems thinking approach and how they can find the right help to put it into effect.

References:

[Louvion 2023] Louvion, C. (2023), Disarming the Blame Bomb: Cultivating a Systems-Thinking Approach.

[Meyer, 2025] Meyer P. (2025), Business productivity and cost cutting: Why slashing staff might not be a quick fix.

[Praslova 2023] Praslova, L.N. (2023), Today’s Most Critical Workplace Challenges Are About Systems, Harvard Business Review.

[Six Sigma.us 2024] Six Sigma.us, (2024), Systems Thinking: A Holistic Approach to Solving Complex Problems.

[Wikipedia, “Systems thinking”] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systems_thinking.