The barriers to solving your business problems: Part 2 – Removing the barriers

By Peter Meyer, Principal Consultant, Elkera Pty Limited

28 July 2025

Many medium-sized organisations face critical strategic challenges. Some are struggling to keep up with rapid growth because their structures and systems haven’t kept pace with their increased scale and complexity. Others, particularly not-for-profits, face pressure to reduce costs while maintaining service levels.

As discussed in the Part 1 article: The barriers to solving your business problems: Part 1 – Problem recognition [Meyer 23 July 2025], these organisations often show recurring symptoms, including:

- Disconnected systems, duplicated effort, and manual work that could be automated.

- Unclear or misaligned roles, leading to duplication, poor communication and unproductive behaviour.

- Insufficient data for managers to make informed decisions.

- Quality issues, customer complaints, and customer attrition.

- Poorly documented processes and slow onboarding.

- Low staff morale, diminished performance, and high staff turnover.

- Limited innovation in products, service delivery or process improvement.

Those symptoms undermine business performance and sustainability over the long term.

Leaders of those organisations often fail to recognise their true problems. Either little is done or they resort to quick-fix measures that do not address root causes.

In the Part 1 article, I examined some of the factors that tend to prevent leaders of medium-sized organisations from recognising the true nature of the organisational challenges that they may face.

I described three barriers to recognition:

- Problems are not visible due to internal structural barriers

- Leadership pressures and incentives promote short-term behaviours

- Lack of systems thinking.

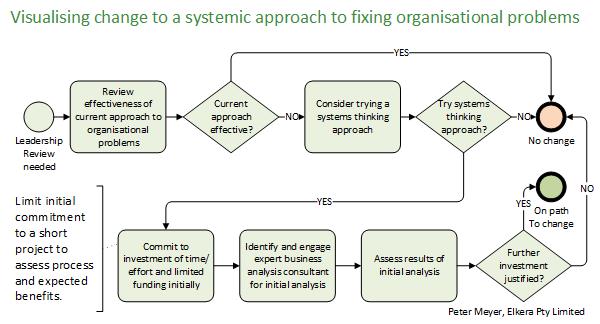

I concluded that a lack of systems thinking is the critical factor that must be overcome if the business is to address its challenges. The first two barriers can be overcome if future actions are based on a systemic approach. That means that business leaders who currently do not adopt a systems thinking approach need to at least recognise that such an approach is necessary. The mind-set of the leadership must change.

In this article, I examine how to make the change from two perspectives:

- How the mind set of leaders can change, and

- How leaders who decide to act should go about finding the expert help they will need to undertake the required systemic analysis of their business.

1. Changing to a systems thinking mind set

1.1 The foundations for change

An effective change process requires at least four of the five elements described in the ADKAR framework [Hiatt 2006]:

- Awareness

- Desire

- Knowledge

- Ability

- Reinforcement.

In this article, I address the first three elements which are necessary to get started.

1.2 Recognising the problem – Awareness

There is no magic bullet for this. Nothing anyone can say will directly convert a non-systems thinker into a systems thinker.

The change can only occur through a process of self-reflection and discovery.

My objective is that, by pointing out the nature of the problems encountered by many medium-sized businesses and the barriers to effective action, some leaders will become aware of a different perspective to the problems within their organisation. If a leader can accept that past actions have not produced the expected outcomes, it is a small step to investigate an alternative approach.

The key elements of that new approach are:

- That the organisation should be viewed and analysed as a whole to understand how operational units work together to deliver the organisation’s outputs.

- When trying to make changes at a work unit level, efforts will be more effective if they are based on an understanding of the whole organisation and how that unit interacts with other units.

- A whole of organisation understanding will provide management with the tools to make better decisions about which changes are needed, how to prioritise them and who should be involved in the planning.

If a leader accepts those elements, they have taken the first step towards systemic thinking, even if the next steps aren’t yet clear.

1.3 Desire for change

Even with awareness, the decision to act requires sustained motivation which can be hard to generate in the face of competing demands.

There are several barriers to action:

- The leader will need to devote considerable effort to convincing other managers and driving a process that some may resist.

- Funding must be obtained for an expert consultant to undertake the detailed analysis.

- It may take longer than desired before results are visible.

Leaders of medium-sized organisations must juggle many competing demands on their time and attention. Whether a leader will act depends on their personal motivations, the expectations that are placed on them by key stakeholders and the incentives under which they operate.

I propose that a desire to act can emerge from these factors:

- When the need for change becomes clear and the cause of the blockage is understood.

- When leaders can see that successful action is feasible.

- When leaders can see that action will benefit the organisation and its stakeholders.

In some way, leaders must shift their approach from immediate problem solving to a strategic focus on achieving a sustainable future for the business.

1.4 Knowledge

If a leader is to get started on tackling the organisation’s problems, he or she must know how to proceed.

The essential knowledge elements are described in this article. Leaders of medium-sized organisations who accept that a systemic approach is required, can access the skills to proceed by engaging an expert business analyst consultant. They will only become converts to systemic thinking if they can see successful outcomes from that approach.

The steps required to identify a suitable expert are described in the next sections.

2. Finding help to address business problems

2.1 What work must be done to get started?

Every organisation is different. Solutions should be tailored to the organisation’s needs. Generally, medium-sized organisations that face the challenges described earlier lack a clear description of how the business works and how its structure relates to its outputs.

On that assumption, most organisations will need to begin by developing a functional model of the business, as it is. That process is described in my article: Growing pains for medium businesses: Why you should clearly define internal business structure [Meyer, 18 June 2025].

At its core, the functional model identifies:

- Primary business functions (also called core functions or value chain activities), being those that directly produce and deliver business outputs to customers.

- Support or secondary functions such as infrastructure management, HR management, technology management, marketing and legal.

- The role primarily responsible for each function.

- Key collaborators who support or contribute to the function.

The functional model is the starting point for more detailed analysis of specific problem areas.

Initially, it not necessary to commit to any further work. The initial project should be limited to demonstrating that a systemic approach will work and that there is sufficient potential for improvements to justify further investment of time and money.

2.2 Who should undertake the work?

Development of the functional model, and the subsequent work that it will lead to, requires the skills of an experienced, objective business analyst consultant. The consultant should have:

- Excellent leadership and collaboration skills to work with team members and other stakeholders

- A deep understanding of business

- A systems thinking, problem solving mindset with the capacity to identify root causes

- Objectivity

- Business process modelling expertise

- A clear focus on the business case for all work undertaken

- Clear written and diagrammatic communication skills.

2.3 Common selection errors

Most leaders of medium-sized organisations face challenges in finding a suitable business analyst consultant. How do you find a capable and reliable consultant?

While some leaders find capable consultants through their personal networks, relying too heavily on that approach has limitations. The pool of candidates is narrow. Trust based solely on prior relationships can mask inadequacies in capability.

Reliance on personal networks arises from two factors:

- A mistaken view that domain business experience is all that is needed to act as an analyst consultant. Hence a previous CEO or senior executive may be considered.

- A form of trust bias or network myopia under which leaders feel more comfortable seeking advice and support from people they know, or who are recommended by people they know.

I wrote about this problem in my article: Hiring a business consultant? Why domain knowledge isn’t enough on its own [Meyer, 25 June 2025].

Personal networks can be highly valuable, but recommendations should be filtered through a clear understanding of actual needs.

Network-based trust lowers perceived risk. However, in many cases, it may actually increase the real risk of hiring someone without the right analytical or facilitation skills.

2.3 How to find and choose a consultant

Here are the steps that I recommend:

- Develop a short brief that describes the organisation and the problem that it faces, taking into account the recommendations provided earlier in this article.

- Consult your network for recommendations, but don’t jump into accepting the first recommendation received.

- Talk to recruiters to find a one who specialises in working with business consultants.

- Search for business analysis consultants through LinkedIn and Google or recruitment sites to look for relevant consultants.

- When you have several candidates, send them your brief and ask them to submit a written proposal for the consultancy. That proposal should describe their expertise, the basis for their fees and how they will go about understanding and meeting your needs. This step is crucial to finding the right consultant.

3. Conclusions

In this pair of articles, I have covered a lot of ground. It began with a rather gloomy picture of medium-sized organisations stuck in a tragic cycle of inaction and quick-fix solutions.

The key insight gained is that the fundamental difference between inaction and action is the presence of a systems thinking approach.

Leaders may not immediately understand how to go about applying a systemic approach but they ought to be able to grasp that such an approach could be the key to unlocking the problems of their organisation.

Once leaders accept that a systemic approach is needed, the path forward becomes clearer. The right mindset opens the door to practical action and the right help makes it achievable.

It is not necessary to make a large commitment without knowing if the benefits will justify the investment. Limit the initial analysis to providing enough information to determine if there are sufficient expected benefits to justify further investment.

References:

[Hiatt 2006] Hiatt, J.M. (2006) ADKAR: a model for change in business, government and our community, First Ed. Prosci Inc. USA.

[Meyer 18 June 2025] Meyer P. (18 June 2025) Growing pains for medium businesses: Why you should clearly define internal business structure.

[Meyer, 25 June 2025] Meyer P. (25 June 2025) Hiring a business consultant? Why domain knowledge isn’t enough on its own.

[Meyer 23 July 2025] Meyer P. (23 July 2025) The barriers to solving your business problems: Part 1 – Problem recognition.