Selection biases affecting leadership recruitment in organisations and how to avoid them

By Peter Meyer, Principal Consultant, Elkera Pty Limited

24 May 2025

Recently, I have been able to observe arrangements for the recruitment of several senior leaders in a medium sized organisation.

Observing the process raised some old questions: Why do organisations so often get leadership recruitment wrong? Why are good internal candidates often overlooked? What should organisations do differently to ensure better recruitment outcomes?”

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic in his excellent book “Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? (And How to Fix It)” (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019) analyses various biases that influence leadership selection without specifically classifying many of them. He focusses on the failure of leadership selection that arises from those biases, with a particular emphasis on the disadvantages experienced by women. He explores the qualities of good leadership and offers some solutions to the selection problem.

There is an adverse selection risk in recruitment due to an asymmetry in information, particularly in relation to external candidates. In our large communities, decision makers lack information on attributes such as competence, capability, integrity and behaviours that are hard to verify directly. Even with information, it is difficult to assess how candidates will perform in the future within the context of the business they are to lead.

To reduce the selection risk, there is a strong tendency for decision makers to rely on culturally embedded heuristics. They rely on signals such as reputation, pedigree, charisma, or prior success to provide a feeling of confidence in decision making. Unfortunately, those signals are wholly unreliable.

We are also susceptible to other the well- known biases (discriminations) based on race, gender and socioeconomic status that can affect recruitment selection. I don’t discuss those biases in this article.

The biases discussed in this article are:

- The Matthew effect or cumulative advantage

- Confidence bias

- Charisma bias

- Halo effect of a specific success.

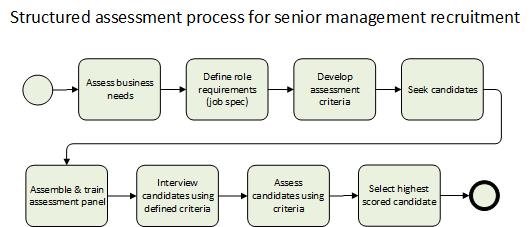

This article describes those biases, explores how they operate and how boards and other decision makers can manage them more effectively. The solution is not to completely reject our instincts but to recognise them and take concrete steps to mitigate their negative effects. The high-level process diagram accompanying this article provides a quick summary of the steps required.

Common biases affecting selection in recruitment

1. The Matthew effect or cumulative advantage

The term “Matthew effect” is taken from the parable of the talents in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 25:29). Use of the term as a label for a bias dates from 1968. According to Wikipedia: “’Matthew effect’ was a term coined by Robert K. Merton and Harriet Anne Zuckerman to describe how, among other things, eminent scientists will often get more credit than a comparatively unknown researcher, even if their work is similar; it also means that credit will usually be given to researchers who are already famous.” See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_effect.

This bias plays out across other sectors:

- In the arts, researchers have shown that artists who exhibit early in top-tier galleries are more likely to maintain elite status, while others rarely break through, even with equivalent output. See: “Quantifying reputation and success in art”, Samuel P. Fraiberger, Roberta Sinatra, Magnus Resch, Christoph Riedl, and Albert-László Barabási, 2018, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aau7224.

- In business, candidates from elite firms or universities often receive preference in hiring and promotion.

Other terms that closely describe this bias include:

- Path dependence: Early steps or decisions significantly shape the direction of long-term outcomes.

- Reputational inertia: Once someone or something is perceived as high-status, that reputation sustains itself regardless of ongoing performance.

- Profile or status bias: Institutional or individual gatekeepers prefer candidates with previously conferred prestige.

This bias is insidious. Internal candidates, currently in more junior roles may be less likely to gain recognition in the face of those biases.

2. Confidence bias

Boards and other decision makers may favour confident, high-profile candidates over more modest but better-suited individuals. Confidence is often treated as competence, particularly in men.

Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) makes it clear that there is no relationship between confidence and competence, citing multiple examples of our self-assessed over confidence (Chamorro-Premuzic (2019), chapter 2.

If confidence is misplaced, it is obvious that an executive selected on the basis of confidence may not perform as expected. Overconfidence may lead to reckless decisions or the executive may simply lack the required capabilities.

There are worse problems. Overconfidence and apparent charisma may be accompanied by negative traits such as narcissism or psychopathy (Chamorro-Premuzic (2019), Chapter 3). Such individuals may do great damage to their organisations and the people who work in them.

3. Charisma bias

This risk is also described as the “charisma myth” (Chamorro-Premuzic (2019), Chapter 4.

Charisma is very difficult to define and to assess, but it is something that we perceive in some people.

As with confidence, there is no relationship between charisma and leadership competence. Rather, it is likely that most effective CEOs are not charismatic. Humility is a valuable quality in a leader.

Like the other biases, the charisma bias leads to the selection of leaders who may not be the most capable of addressing the challenges that organisations may face. It is likely to lead to the overlooking of more competent, less visible candidates. Often such candidates are already employed by the organisation.

4. The Halo effect

This term was first used by US psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1920 and describes the tendency to make specific inferences on the basis of a general impression (Phil Rosenzweig, “The halo effect, and other managerial delusions”, 2007).

Rosenzweig (2007) applies the term “halo effect” very broadly: “…many of the things that we commonly believe are contributions to company performance are in fact attributions. In other words, outcomes can be mistaken for inputs.”

More specifically to the topic of this article, society and decision makers often attribute general wisdom or cross-domain competence to individuals who have achieved success (e.g., entrepreneurship, elite consulting) or wealth in a specific domain, regardless of its relevance to new contexts. This assumption can override careful consideration of domain knowledge, interpersonal skills, or strategic fit.

Common examples include the appointment of successful entrepreneurs or athletes to leadership roles outside their domain, where their instincts and habits may not translate.

This bias can lead to poor recruitment decisions, especially in complex or technical environments.

An overlooked factor: The personal interests of the selectors

From my observations, the listed biases can be accentuated by the personal interests of decision makers. Board members and selection panels often make leadership selections under scrutiny. This is especially evident in nonprofit, arts, and public sector organisations where selectors are under scrutiny from political, bureaucratic or donor related sources.

In such environments, board members or other decision maker’s reputations are on the line. They may be eager to signal to various groups that they have made a wise decision. Understandably, they may favour candidates who are easily defensible choices based on visible credentials or a familiar leadership profile. Such choices are less likely to attract criticism, even if they are not the optimal fit. Internal or other candidates with good potential may be overlooked.

Through the influence of these biases, the appearance of a sound decision can become more important than the substance of it.

Can these selection biases be overcome?

Unfortunately, there is no reason to believe that we can simply will ourselves out of these biases. These biases are not moral failings. They are natural responses to uncertainty. Perhaps, over time and with practice, we could become less susceptible to some of them. Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) at p. 118 assesses that we cannot avoid taking them into account.

The best solution is to work around the biases by using a structured interview process in place of an unstructured process.

Practical steps to overcome the selection biases

Here are some practical steps for decision-makers:

1. Start with a problem definition

To begin the recruitment planning process, clearly define the strategic and operational challenges the organisation faces. Is the business in difficulty and, if so, why? Is it entering a new market? Does it have a particular culture problem? Different challenges demand different kinds of leadership.

2. Develop role-specific requirements

Based on the problem analysis, define specific requirements for the role. These should include both intellectual and technical capabilities as well as the leadership behaviours needed to meet organisational objectives. Treat this like any other business requirements document.

Too often, job descriptions are based on recycled job descriptions from prior recruitments or from other organisations and are not based on a real analysis of the organisation’s problems and needs. Such job descriptions provide no basis for a structured assessment.

Irrelevant signals such as confidence, charisma and the like should not form part of the role requirements (Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) at p. 131).

3. Use structured interview questions

Design assessments and interview questions that map directly to the requirements. Use structured scoring, behavioural questions, or real-world problem simulations. This creates a clear basis for comparison without reliance on the common selection biases.

Standardised comparisons should be used, where the questions are asked in the same way for each candidate to ensure consistency in the data. Interviewers should be trained to interpret answers in a consistent manner. (Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) at p. 131).

4. Use psychometric tests to measure psychological characteristics

It is fairly common for organisations to use these tests. In my own observation, they do not always seem to lead to a good outcome, although it is likely they weed out some of the more unsuitable candidates. Perhaps the limitation is that the tests often are not applied on a foundation of clear requirements. According to Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) at p. 120, these tests are the best predictor of job performance.

5. Create diverse selection panels

Ensure that hiring or promotion panels include personnel with varied perspectives and who are encouraged to challenge each other constructively. It is important to minimise the influence of any one personality.

Conclusions

In most leadership selections, decision makers face a selection risk. How do they assess critical qualities in candidates (e.g., expertise, competence, psychological attributes, values, potential)? In an attempt to avoid that risk, decision makers rely on proxies (biases) to filter options during the selection process. Those biases create a new set of risks.

The effect of those biases is that decision makers still may fail to secure the best leadership. Less visible, but worthy, candidates may be overlooked. Inequality may be perpetuated. Employees who consider themselves to be unfairly overlooked may leave the organisation or quietly quit.

Further, decision makers acting under scrutiny may face reputational risk from their selections. Seeking to minimise their risk of criticism, they may prioritise candidates with reputational attributes that make them easily defensible choices over better candidates who lack those attributes.

Boards and executives undertaking recruitment should be aware of those biases and take a systematic approach to minimise their adverse effects.

Recruitment should be undertaken with the same rigour as is applied to strategic and system related decisions. The fundamentals of a solution are to analyse business needs, define role requirements, develop a structuring evaluation and apply that evaluation process in a consistent way with trained personnel. That approach is described in the high-level process diagram that accompanies this article.

The outcome ought to be better leadership and more equitable treatment of talented people within the organisation.