Set up your organisational change project for success before the work begins

By Peter Meyer, Principal Consultant, Elkera Pty Limited

19 August 2025

Most organisational change projects fail. The problem affects all change projects including organisational restructures and process automation with software tools. That dismal record is even worse for attempted AI based process improvements (Ryseff et al., 2024).

Analysts point to a failure to communicate project urgency (Kotter, 2014) and weak internal communication (Elving, 2005, cited in Yue et al., 2019) as common causes of project failure.

The underlying factor in those explanations is related to communication with employees. Employees don’t trust the process.

From my observations, the underlying sources of communication failure include:

- Many projects lack clear objectives or defined business benefits.

- Project leaders often fail to properly identify and consult with all relevant stakeholders during change planning and requirements elicitation.

- Communications with stakeholders often are not conducted transparently. Leaders often fail to tell employees what is really planned or to seek their genuine input about how changes can be effective. Leaders assume that employees will sufficiently comply when presented with a new system or new tools.

Unclear objectives, poor stakeholder engagement, and opaque messaging leave employees sceptical before the real work starts.

It is extraordinarily difficult for a change project to succeed in the face of employee indifference or resistance. Research confirms that assessment (Reichers, et al., 1997; Yue et al., 2019).

Change projects require the willing support of affected employees if they are to succeed. The pre-conditions to effective change under the commonly used ADKAR framework are acceptance and desire (Hiatt, 2006). Many researchers use the term “openness to change” as the pre-condition (Yue et al., 2019).

In an earlier article: Assembling the right teams for systems improvement projects (Meyer, August 2025), I discussed the need to establish a clear project charter and the need to identify all stakeholders with the right people involved in requirements elicitation.

In this article, I dig deeper into the employee consultation process. Getting the right people involved in requirements elicitation process is a necessary step, but it not sufficient. It does not address the underlying problem of securing the willing support of employees for the proposed change.

Miller et al., 1194, as cited in (Yue et al., 2019) describe employee openness to change as a “necessary initial condition for successful planned change”.

The question is: how is openness to change secured? In my experience, and strongly supported by research, the essential ingredient is trust (Yue et al., 2019).

Trust is either present or it is not. There can be a range of carefully crafted communication activities, but if they don’t engender trust, they are not effective. Trust is substantive, rather than performative.

In this article, I describe how leaders can build employee openness to change by focussing on establishing and maintaining trust throughout the communication process.

1. What is change?

Change is any alteration to the environment that requires internal organisational responses to accommodate new procedures, processes, culture or personnel. Examples include: structural reorganisation, process improvement and process automation using new software, including with AI tools.

Change may be planned or it may be required in response to a crisis, such as occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic or a major economic disruption. In this article, I focus on planned change, but many of the principles involved also apply to change in response to a crisis.

Change begins as soon as the organisation starts to conduct an analysis of the current organisational structure and production processes to assess areas for improvement. An example is the undertaking of a functional modelling process that I have described elsewhere (Meyer, June 2025).

2. The effects of change on employees

Change puts employees in a vulnerable position and creates uncertainty. Job security and employment conditions will rank high among employee concerns (Gustafsson, et al., 2020).

Thus, the earliest days of a change initiative often determine whether it will succeed or stall. In my experience, before the first stakeholder interview or workshop, or a process is mapped, employees are already making assessments, and forming opinions and expectations. That is borne out by research (Bordia et al., 2004).

Those first impressions matter. In organisations with a strong record of successful projects, staff may simply wonder: What will this mean for me? Will I be involved? Is my role changing?

In organisations where past projects have failed or delivered poor outcomes, harsher questions may be asked: Will we be told what the project is about? Are out jobs safe? Will our views be heard? Will we be treated fairly? Or, will this be another costly distraction?

Behind every one of those questions lies a decisive factor: trust.

3. Trust is the foundation for organisational change

Trust in this context is defined by researchers as: “employees’ willingness to be vulnerable to their organizations’ actions based on the belief that their organizations have integrity, are dependable, and competent” (Yue et al., 2019).

It is interesting that authors of well-known change frameworks: Kotter (Kotter, 2014) and ADKAR (Hiatt, 2006) do not highlight the importance of trust.

Yue et al., (2019) show that trust strengthens openness to change, and that transformational leadership and transparent communication cultivate that trust. In short, communication and leadership only work if they build trust.

If we stop to think about it, those findings make intuitive sense. When leaders either act secretively or make statements that sound encouraging but are unconvincing to employees, it should be no surprise if employees exhibit apathy or, at worst, cynicism and resistance.

I have observed this personally in multiple organisations. Projects with poorly defined objectives and opaque messaging fail. Communications to employees are crafted to obscure what is really happening until decisions are finally announced. The assumptions appear to be that employees will either not notice or they can be deflected. Those assumptions are invariably wrong.

By focussing on trust, leaders can unlock employee collaboration and the desire to see change succeed.

4. The direct effects of low trust

Low trust during organisational change tends to generate negative emotional states that directly undermine openness to change. In my observation, and confirmed by research, when employees lack confidence in leadership or communication, they default to defensive and disengaged behaviours that directly obstruct openness to change (Edmondson, 1999; Yue et al., 2019).

Low trust typically triggers five damaging emotional states:

Low psychological safety – When trust is missing, employees avoid speaking up, asking for help, expressing disagreement, or admitting mistakes. The result is silence, poor knowledge sharing and reduced participation (Edmondson, 1999).

Uncertainty – When information is lacking or is unreliable, uncertainties may arise in relation to:

- organization-level issues, such as reasons for change, planning and future direction of the organization, its sustainability, the nature of the business environment the organization will face.

- changes to the inner workings of the organization, such as reporting structures and functions of different work-units.

- job security, promotion opportunities and changes to the job role. This is the most stressful.

Fear of job loss leads to defensive behaviour and information hoarding (Bordia et al., 2004; Jimmieson et al., 2004).

Resentment (perceived unfairness) – Where processes are opaque or appear to lack fairness, employees become resentful. Resentment leads to lack of organisational commitment and withdrawal such as passive or active resistance (Colquitt et al., 2001).

Low motivation and engagement – Without trust, employees doubt the legitimacy of the project’s goals. They may comply superficially but rarely commit effort or creativity. Motivation collapses, making genuine participation unlikely (Yue et al., 2019).

Cynicism – Employees who have experienced past broken promises or failed initiatives often develop cynicism. They assume management “won’t follow through,” which erodes morale and reduces effort (Reichers, et al. 1997).

Trust is the best antidote to those emotions.

5. How is trust built?

5.1 The three principles that underpin trust

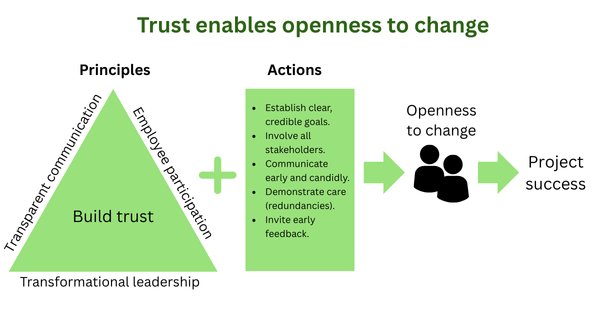

Research confirms that three core principles must be followed to build trust:

- Effective leadership

- Transparent communications

- Employee participation in decision making.

Each of these is discussed in the following topics.

5.2 Effective leadership

To be effective, leaders should:

- Communicate collective purpose and values, demonstrate confidence and determination, and act as a role model.

- Provide a vision for a desirable future that motivate followers to perform to higher levels and achieve common objectives.

- Demonstrate personal care, empathy, sensitivity and individual consideration for the needs of employees.

- Stimulate employees to think outside the box, challenge old assumptions, and promote innovation.

That effective leadership is also described as “transformational leadership” (Yue et al., 2019).

Every project requires a sponsor. The project sponsor should be a person with the authority to make decisions and allocate resources to the project. In projects other than local, small team initiatives, it is important that employees perceive that the project has top leadership support.

The sponsor should be consistently visible and responsible for important communications. The sponsor should speak at the project launch, articulate the project goals and provide periodic updates.

The sponsor and other senior leaders should attend key workshops, visibly listening to feedback.

5.3 Transparent communications

Transparent communications:

- Provide truthful, substantial and useful information.

- Involve employees in identifying the information they need.

- Include both positive and negative information and avoid any attempt to manipulate employees’ perceptions and interpretations.

(Yue et al., 2019)

5.4 Employee participation in decision making

If employees are involved in decision making about the tactical aspects of change, that will have a positive effect and reduce employee uncertainty (Bordia et al., 2004). The effect is particularly significant when the issues directly affect them.

Participation does not mean that employees decide the outcome. The point is that they want to be heard. The act of carefully listening to employees and providing feedback so they consider they have been heard has positive effects on their emotional state and willingness to cooperate (Itzchakov, et al., 2018).

6. Applying the three principles in your project planning

Every change project is different. Some may proceed quickly to reorganisation while in other cases reorganisation may occur only after a period of analysis and assessment of options. Thus, it is possible only to provide broad recommendations based on the three principles.

If the project involves a period of analysis prior to development of a specific change proposal, leaders won’t be able to inform employees of the details of likely changes. However, it is critical that they do provide accurate information and acknowledge what is currently unknown.

Based on the three principles described in the previous section (section 5), critical actions to build trust should include:

A. Establish clear, credible goals

If the project is to succeed, there must be a compelling vision, supported by a business case. Full details of the changes may not be known at the outset, but there must be enough information to justify the initiation of a project.

It is critical to develop a project charter for every project, as I discussed in Assembling the right teams for systems improvement projects (Meyer, August 2025).

B. Involve the right people from the start

Based on the project scope defined in the project charter, identify all stakeholders likely to be affected. There will be multiple groups of stakeholders with different interests. Some may be included as subject matter experts for process analysis and requirements elicitation. Other employees likely to be affected by the project must also be involved.

C. Communicate early, clearly and candidly

Actions to build trust must begin with the very first information that is communicated about the change project.

Explain the goals of the project, how they will benefit the organisation and its people, what it will cover, and what is out of scope. This can be achieved by sharing the project charter or key elements of it.

D. Demonstrate care where redundancies or role changes are likely

If redundancies are likely, great care is required to manage that information effectively. Employees at risk are likely to be aware of that risk. It is better to tell employees whether role changes or redundancies are possible than to allow speculation and distrust to develop.

If redundancies or role changes are likely, decide what support services can be offered, such as redeployment, training, employment support, career counselling and similar matters. Inform employees of proposed support plans.

E. Invite employee feedback early in the planning process

Establish a process to obtain employee feedback promptly after the initial communication. That process may involve meetings or a Q & A channel, depending on the circumstances.

Invite all affected employees, not just process experts and managers, to early feedback sessions.

There are two goals for obtaining early feedback:

- Identify issues of concern to employees as soon as possible so they can be taken into account in further planning.

- Establish participation in decision making so that employees feel that they are being heard, before negative emotions take hold.

7. Taking your project to completion

The preceding sections have described how to lay the foundations for a successful project based on the establishment and preservation of trust.

All the elements described are well known project management practices.

If leaders focus their actions on building trust, their actions are more likely to be much more effective than if they simply work through a list of activities without being clear about the real objectives.

The trust building actions described will lead the organisation directly onto the path to successful change, such as that mapped out in the widely referenced ADKAR change management framework (Hiatt, 2006). In the first instance, it will create:

- Awareness, where employees will know why the change is needed and what it involves.

- Desire, where employees will feel safe and see personal or collective benefits in the proposed change.

The foundation of trust will then underpin fulfilment of the subsequent ADKAR stages: knowledge, ability and reinforcement.

8. Conclusions

Project failure is not employees’ fault. It is leadership’s responsibility to create the conditions for success. Few factors matter more than trust. If trust is present, standard change frameworks like ADKAR can work. If trust is absent, even the best-designed process is likely to fail. For medium-sized organisations, building trust from day one is the single most important predictor of success.

With trust as the goal, all project planning activities are directed towards achieving a substantive outcome, rather than a performance of working through a list of planning tasks. The focus on trust provides substance and discipline to all project activities, beginning with development of the project charter, that will greatly enhance the prospects of project success.

Before your next change project begins, consider whether you have in place the foundations and practices to build and maintain employee trust from day one. If you don’t, your project may be at risk. My work with clients focuses on helping them to trust-building practices from day one of project planning.

Checklist

Download the accompanying checklist for actions listed in section 6.

References

(Bordia et al., 2004) Bordia, P; Hobman, E; Jones, E; Gallois, C; Callan, VJ, Uncertainty During Organizational Change: Types, Consequences, and Management Strategies, Journal of Business and Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 4, Summer 2004, <https://www.academia.edu/129918170/Uncertainty_During_Organizational_Change_Types_Consequences_and_Management_Strategies>.

(Colquitt, et al., 2001) Colquitt, JA; Conlon, DE; Wesson, MJ; Porter OLH; Ng, KY, Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research, Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, Vol. 86, No. 3, 425-44, <https://leeds-faculty.colorado.edu/dahe7472/Colquitt%202001.pdf>.

(Edmondson, 1999), Edmondson A, Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Jun., 1999), pp. 350-383, accessed at: <https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Group_Performance/Edmondson%20Psychological%20safety.pdf>.

See also: Edmonson A, Managing the risk of learning: Psychological safety in work teams (March 2002), <https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/02-062_0b5726a8-443d-4629-9e75-736679b870fc.pdf>.

(Gustafsson, et al., 2020) Gustafsson, S; Gillespie, N and Dietz, G, 2020, Preserving Organizational Trust During Disruption, Organisational Studies, Volume 42, Issue 9, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620912705>.

(Hiatt, 2006) Hiatt, JM, 2006, ADKAR: A model for change in business, government and our community, Prosci Inc., Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

(Itzchakov, et al., 2018) Itzchakov, G and Kluger, AN, The Power of Listening in Helping People Change (2018) <https://hbr.org/2018/05/the-power-of-listening-in-helping-people-change>.

(Jimmieson, et al., 2004) Jimmieson NL, Terry DJ, Callan VJ, 2004, A Longitudinal Study of Employee Adaptation to Organizational Change: The Role of Change-Related Information and Change-Related Self-Efficacy, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology (2004) 9 (1): 11-27, accessed at: <https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Deborah-Terry-3/publication/8938863_A_Longitudinal_Study_of_Employee_Adaptation_to_Organizational_Change_The_Role_of_Change-Related_Information_and_Change-Related_Self-Efficacy/links/0fcfd50f1d807567ae000000/A-Longitudinal-Study-of-Employee-Adaptation-to-Organizational-Change-The-Role-of-Change-Related-Information-and-Change-Related-Self-Efficacy.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=Y8xyfdltgF78R4IpX4MTzRe_iDGcls1iH6rXYvqP1Cs-1755315998-1.0.1.1-NKMoPOj8eubtF4aXrTMNbL6abGZBnLD2.RMZZEe7dbc>.

(Folger and Skarlicki, 1999) Folger, R; Skarlicki, DP, Unfairness and resistance to change: hardship as mistreatment, Journal of Organizational Change Management (1999) 12 (1): 35–50, <https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910255306>.

(Meyer, June 2025) Meyer, P, 2025, Growing pains for medium businesses: Why you should clearly define internal business structure, <https://elkera.com.au/define-business-structure-with-functional-model/>.

(Meyer, August 2025) Meyer, P, 2025, Assembling the right teams for systems improvement projects, <https://elkera.com.au/the-right-teams-for-systems-improvement-projects/>.

(Reichers, et al., 1997) Arnon E. Reichers; AE, Wanous, JP; and Austin, JT, Understanding and Managing Cynicism about Organizational Change, The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005) Vol. 11, No. 1 (Feb., 1997), pp. 48-59, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4165371>.

(Ryseff et al., 2024) Ryseff, J; De Bruhl, BF Newberry, SJ, 2024, The Root Causes of Failure for Artificial Intelligence Projects and How They Can Succeed, Avoiding the Anti-Patterns of AI, <https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2680-1.html>.

(van den Heuvel et. al., 2013) van den Heuvel, M; Demerouti, E; Bakker, AB; Schaufeli, WB, Adapting to change: The value of change information and meaning-making, Journal of Vocational Behaviour Vol 83, Issue 1, August 2013, pp 11-21, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0001879113000493>.

(Yue, Men & Ferguson, 2019) Yue, CA; Men, LR; Ferguson, MA, Bridging transformational leadership, transparent communication, and employee openness to change: The mediating role of trust, Public Relations Review 45 (2019) 101779, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0363811119300360>.